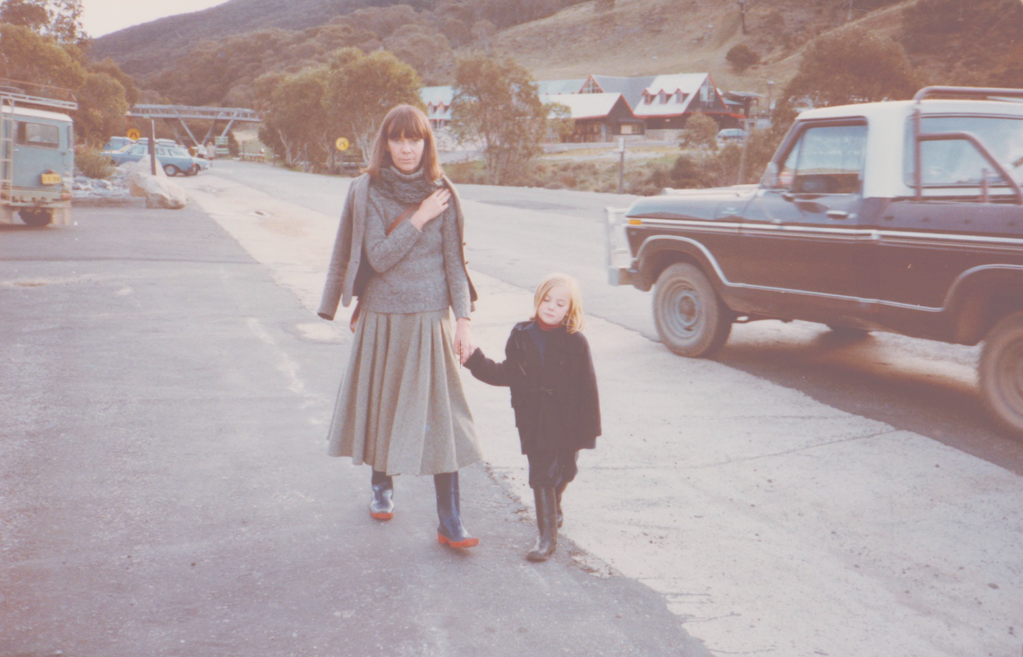

In 2000, after 12 years of severe depression my mother Chrissy committed suicide. The night I heard she died I lay in my bed, hair still wet from the shower that had been interrupted by the call, with a deep sense that I hadn’t begun to feel the pain. I lay there, age 22, across the world from where she lay, counting off the events in my life I was going to live through without her. Just six weeks into my new life in London, the tether to my old life, my home, was gone.

I made the 24 hour plane journey back to Melbourne, I cried, swapped stories, hugged and even laughed. Her funeral service was jammed to the rafters, with the many friends she had made over her lifetime, all of them in disbelief that this gentle soul’s life had ended this way. I thought about how lucky I had been to have her until I was 22, instead of 14, when the threat of her suicide was with us almost daily. There had been so many good times between 14 and 22 and I was grateful for every single one of them.

I returned to my life in London, my new job, new flatmates and friends. It was a rollercoaster of a year, grieving, living, working, stretching my wings, achieving, breaking up, making choices. I remained grateful for the mum that I had had, not slipping into anger, as many had supposed would happen. Buoyed on perhaps by the simple fact that the worst had happened and here I was, living, breathing and still able to experience joy, relived that she wasn’t suffering anymore. Yet a nagging feeling remained that I had yet to feel the full impact of her loss. That I wouldn’t be capable of feeling it till I was a mother myself. I knew it so instinctively that I didn’t even question it. Grieving was a process and I was only part of the way through.

Ten years later I held my son Arthur in my arms for the first time. He had arrived a month early, needing to be resuscitated and we had ended up with a week long stay in a hospital ward over looking Big Ben and the Thames. I missed her. I had known I would, and I missed her with a deeper longing then I had felt since the day she died. In the months that followed I thought of her constantly. I thought back to all the stories of our births and babyhoods. Luckily for me, my mother had been a storyteller, a woman so in her element in those early years of motherhood that she liked to recount all the tales to us as we got older. I had many questions that had no answers of course, and it often made me sad to see and hear the support that other new mothers received from their own mothers. Occasionally a feeling, a discomfort I couldn’t quite put my finger on would hang around me until I stopped and acknowledged it for what it was. Envy. Not a feeling I had had much experience with until that point and it took me a while to admit to myself that was what I was feeling. I learned to recognise it for what it was. Latent grief.

In Arthur’s second year I was heavily pregnant with my daughter and facing something altogether more confusing. My son’s development had slowed, virtually to the point of stopping. He was increasingly further behind his peers and becoming extremely difficult to cope with. He couldn’t follow instructions, seemed interested in only a few types of play, didn’t have any words and lashed out whenever he was confused or upset. Friends talked about how things were finally getting easier and how wonderful it was to watch their children soak information up like sponges. Nothing could have been further from my experience. By the time his sister Agnes was a few months old I had to admit that something was very wrong.

Over the following year, waiting for appointments, researching, opening our eyes to what was going on, it was as if my mother had died all over again. Arthur was diagnosed with Autism shortly after his 3rd birthday and I grieved more for my mother in the months afterwards then I had in the previous ten years.

My marriage was falling apart, my child seemed incapable of learning what his peers found natural and easy, and all I could do was wish my mother was there to tell me everything would be ok. Jealousy tore through me to the point I didn’t recognise myself. I saw families that were connected and healthy and developing, other mothers who had support for children who didn’t even seem to need any. Comparison crept into my thoughts in a way it never had in my life. I lay in bed at night wishing that I had my mother by my side.

It was on those nights I lay there, that I knew that I would get to a place of acceptance one day. That I would feel happy and joyful again. I knew it yet I wasn’t there yet and I wanted to rush through this process, so I could leave the jealousy and grief behind and be happy again. But it was a process that would take time and a very large change of mindset. I would need to admit to myself that the problem was within me and my expectations of motherhood. I was not going to be able to enjoy family life until I got rid of any and all preconceived ideas about what it would look like.

That was more then 3 years ago now. And I was right. I was going to get through that time. My life is filled with joy and hope, just as most of my life has been, not because Arthur is less autistic then he was then but because I have accepted we are on a different path. The grief that I felt for my mother during that time was the grief that had been lying, waiting for me. It was not brought on by the big milestones she would miss, the weddings, the births, the new jobs and achievements. It was the times I would not know how I could go on, the unbearably hard times, where the blows are doubled because she’s not there to hold my hand. She dies all over again, each time I’m howling on the kitchen floor. At the end of my marriage, at each road block in Arthur’s development, at each difficult decision I need to make for him that I don’t feel qualified to make, each time I have to fight for the services he needs.

I’m at a point now where I can recognise the pain. It doesn’t creep up on me. I see it and I can say, “Hello, it’s you again, I know why you’re here”. I accept the pain and know that I can live side by side with it. I remind myself why I feel it. I had a mother I loved so deeply that I will always feel her loss. I feel it because if she were alive, she would have been the person I turned to. And I am so lucky to have had someone like that in my life for 22 years.

Penny is 39-years old and originally from Melbourne, but now lives in London with her two children, Arthur aged 7, and Agnes aged 5. More about her can be found here @pennywincer and here applesandoptomists.com.