What no one ever told me about grief was that no matter how much time passed, no matter how much I tried to work through it (hello therapy), no matter how much I thought I’d got away with it, I would never be able to escape it. That complex web of emotions, unanswered questions and sheer gut-wrenching sadness would always be there, lurking away, poised ready to pounce when I least expected it. And bamm, just like that, out it would come armed with the cruel ability to turn one of the happiest moments of my life upside down.

That moment came early on a Tuesday morning in the summer of 2011 when my son was born. As I sat with him in my arms I reached for my phone to call my mum. I mean, that’s what you do when you’ve just had baby isn’t it? You call your mum. Only then it hit me, like a truck, like a freight train, like all the cliches you can think of. My chest suddenly heavy, an ache in my throat, my tired eyes filling with tears. For in the most perfect, then unbelievably heartbreaking split second, I’d completely forgotten that I couldn’t phone my mum. Like some cruel twist of fate my exhausted delirious brain had somehow let me momentarily forget that she had died 10 years ago.

I wasn’t expecting to feel like this. Saying I’d missed her since she died would be an understatement. I’d missed her unimaginably so – when my first book was published, when I got married, when I fell pregnant, when my younger brothers married – each of these landmark events were bittersweet, overshadowed by a longing for my mum to be there, too. But it had been over 10 years, and time and therapy had both been great healers. Or so I’d thought. Because suddenly there I was, a mother, holding my son, her grandson, and all I could think was, where’s my mum when I have, quite literally, the most important news of my life to share with her? And how am I meant to do this on my own without her knowledge and wisdom?

My mum died when she was 52 and I was 23. Like so many others it was cancer that took her. I didn’t know she was going to die because she promised me she’d be ‘fine’ (her words, not mine) and by the time I realised that that wasn’t entirely true it was pretty much too late. A phone call, a mad dash to be by her side, and ‘Charlotte, sweetheart’ were her final words. As a single mum with three kids she’d been strong, resilient and resourceful, and she’d never given up.

Our relationship had been challenging at times (what mother daughter relationship isn’t) and while we were close and I talked openly to her about life, we also fought. I’d moved out of home at 18 and things started to improve, but then she got sick, and then she died. All I remember feeling at that time was regret – I’d never be able to undo my teenage behaviour, we’d never have a chance to rebuild our relationship – and a sense of yearning – I wanted to experience that special grown up mother-daughter bond, that bond that was more like a friendship. Instead our relationship will forever remain in that in-between moment – not quite mother and child, not quite friends – making me feel at best, wistful, at worst, like crying my eyes out and shouting ‘life’s not f***ing fair’.

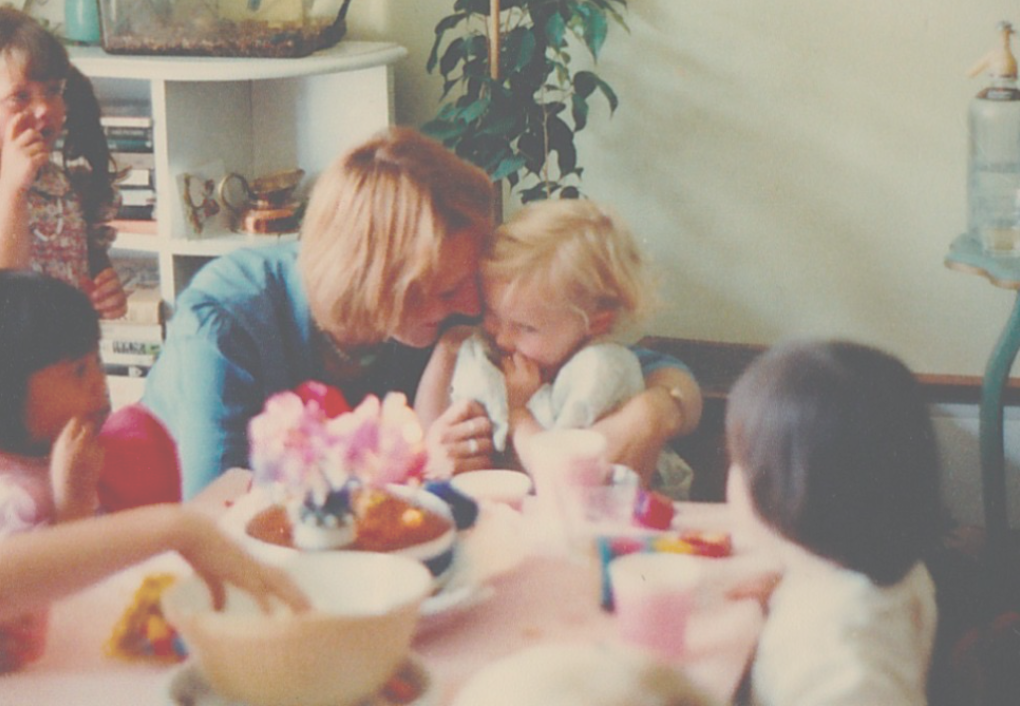

I didn’t know it at the time but what was to follow in the days, weeks and months after my son was born was a journey of incredible love and immense sadness. I was falling in love with my beautiful son on the one hand, while on the other I was grieving for the loss of my mum all over again, talk about conflicting emotions. There were feelings of joy, feelings of regret, a sense of longing and oh so many questions – What was I like as a baby? Did I sleep in my parents bed? Did my mum struggle with breastfeeding? How did she cope without her mum around? And what the hell does green baby poo mean? I rifled through old boxes of pictures, I found letters and scrapbooks, and I read and re-read my baby book. I started a book for my son too, I wrote a diary (each day for a while), I documented all his firsts, and took more photographs than I care to admit. I wanted to make sure I got it all down for him, just in case.

Fast-forward to today, my son is now four and a half and somehow I have managed to get this far without her. I’ve learnt to feel confident in my ability as a mother, despite not having her guidance, because even though she’s not here I recognise so much of her within me, like she’s living through me. My sister-in-law is also navigating motherhood without her mum. She lost her mum when she was just nine years old but she says she’s never felt closer to her than she has since having her daughter two years ago. “Becoming a mum has been like becoming my mum,” she tells me. “I hear myself saying things to my little girl that she said to me, I sing the same songs as she did, and I feel similar to the way she did about being a mum – I really enjoy it, I find it fulfilling – which is so comforting. In a way my mum and I have more in common now than we have ever have which has brought me far closer to her, and that feels really nice.”

And then there’s my friend who lost her mum when she was 21. She has two young kids of her own now and in some way feels that her mum is there with her too. “I actually felt quite confident when I became a mum. It felt so right and I think that was due to my mum, she was happy as a mum, she believed she could do it, and I think I had that in me. Now It’s like she’s somehow here, like she can see what I’m doing and is guiding me through,” she explains. “I desperately miss her though. Even at 21, my age when she died, I was too caught up in my own life to think of asking questions, but I have so many questions I wish I could ask her now.

That’s the thing, when you’re young, in your teens, your 20s unless you’re having kids you don’t think to ask questions about being a mum, you’re mind is occupied by an entirely different set of priorities. It’s only when you become a mum yourself that thoughts of your own mum’s experience of motherhood and questions about your childhood become so important, yet sadly, if you’re motherless, remain frustratingly unanswered.

I was speaking to another old friend recently who lost her mum when she was 24. She now has two daughters and we were talking about the whole ‘not knowing stuff’ thing. “When I got pregnant it really hit me that my mum wasn’t there, that my child would never meet her, that she couldn’t tell me about her pregnancies, and that I would never know what I was like as a kid,” she tells me. “My dad remembers little as he worked away a lot and while I have two older sisters who remember some things, it’s not the same. So now I collect all sorts of things that my girls have made and done and we try to make sure there are lots of pictures of me and them together. I also take videos of the girls and make sure that I talk too because I wish I could hear my mum’s voice now – I hate it, but I hope that one day my girls will appreciate it.” It’s funny because I do exactly the same thing, for exactly the same reason.

As I approach the 15th anniversary of my mum’s death later this month and reflect on my experience of motherhood without her, and that of my motherless friends, I am reminded once again that life is short and that every moment is incredibly precious. There are lots of things I’ve missed, from the practical – what I’d give for a break in the day-to-day relentlessness of motherhood, a morning here, an afternoon there, a drop off, a pick up, an overnighter even – to the two thousand unanswered questions (of varying importance)… Have I had chicken pox? Was I a late walker? Do you forgive me for my teenage behaviour? How many bananas can a child eat in one day? – to sharing those big moments… First word, first tooth, first steps, first birthday, first day at school. Each event has passed by just ever so slightly tinged with sadness because that unmade phone call, that unsent text or that unshared photograph always serve as a gentle reminder of my loss.

I also miss my mum’s knowing voice at the end of a phone, the easy comfort of her presence in my home, her unconditional love and patience, and her reassurance that as a parent I’m doing OK. But I do take huge comfort in knowing that through me her spirit and legacy will live on. Every night I sit on the edge of my son’s bed, I stroke his head, and tell him that I love him, because that’s what she did to me. I call him sweetheart and poppet because that’s what she called me. When he’s sick I give him marmite on toast because that’s what she gave us. And each Christmas I make an enormous pavlova, just like she did, because my mum was Australian and that’s just what you do.

This article was first published in Motherland in January 2016